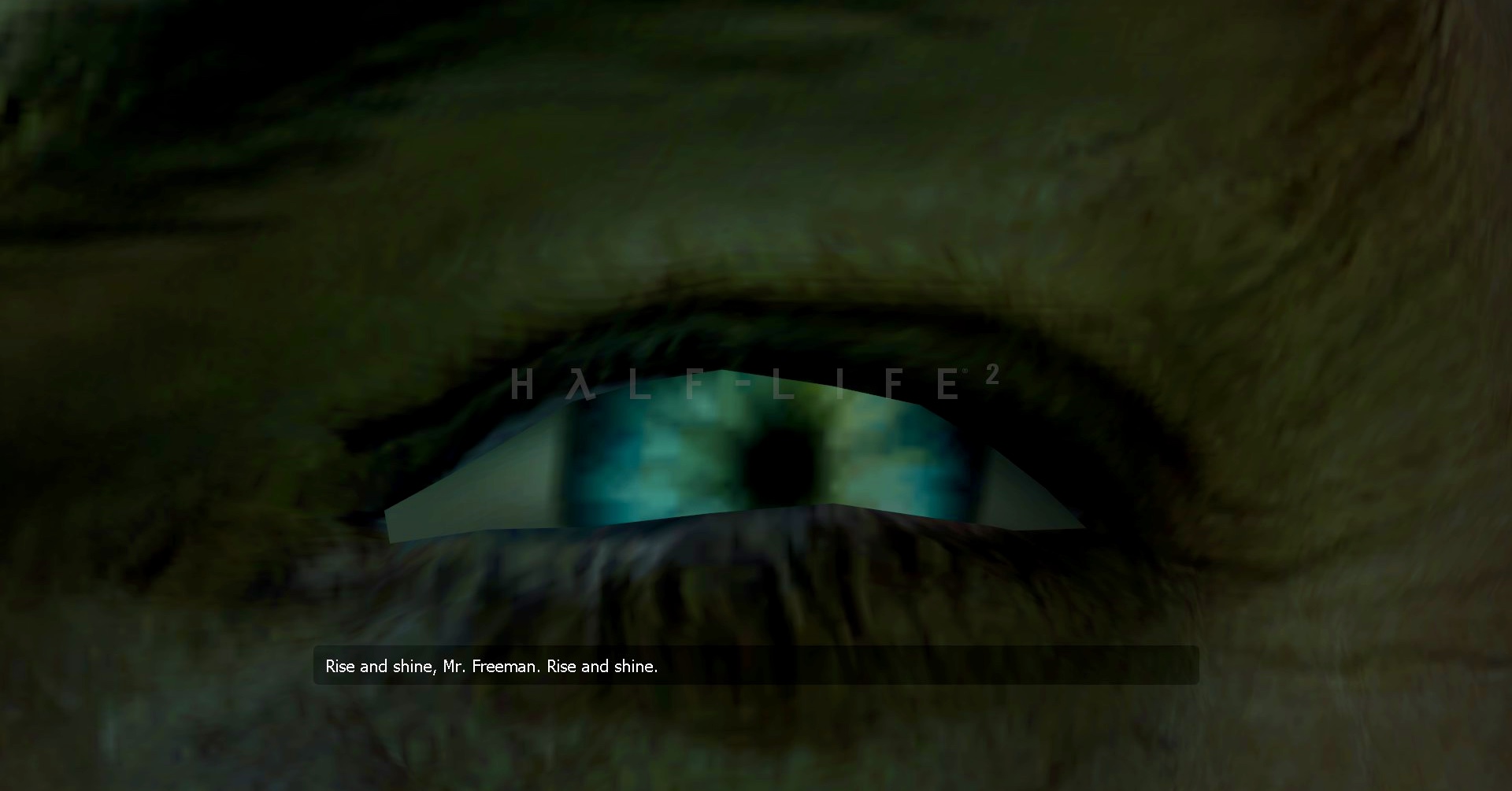

When Half-Life 2 (Valve) released in 2004, it modernised game and narrative design alike. Like its predecessor it refrains from telling its story through cut scenes and non-connected gameplay but rather sets players at the forefront of the action. This is thanks to use of scripted events and characters that players care about and with whom they engage in conversation (or these characters talk to the main protagonist). Such narrative devices were quite new and revolutionary in this time and helped immerse players in a frightful and depressing gameworld. In addition, the game took inspiration from George Orwell’s masterpiece Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) and translated the traditional dystopian plot framework of literary works and films to video games.

Half-Life 2, in other words, is the classical video game dystopia. It involves players in a nightmarish gameworld and storyline, but it also sets them at the forefront of the resistance, transforming players into catalysts of change and transformation. Specifically, the game’s beginning is noteworthy in this regard. For it introduces players to an organic world and sets up the plot to come (the clash between the dystopian regime of the COMBINE / DR. BREEN and the RESISTANCE with Gordon Freeman and the player leading the counter-narrative).

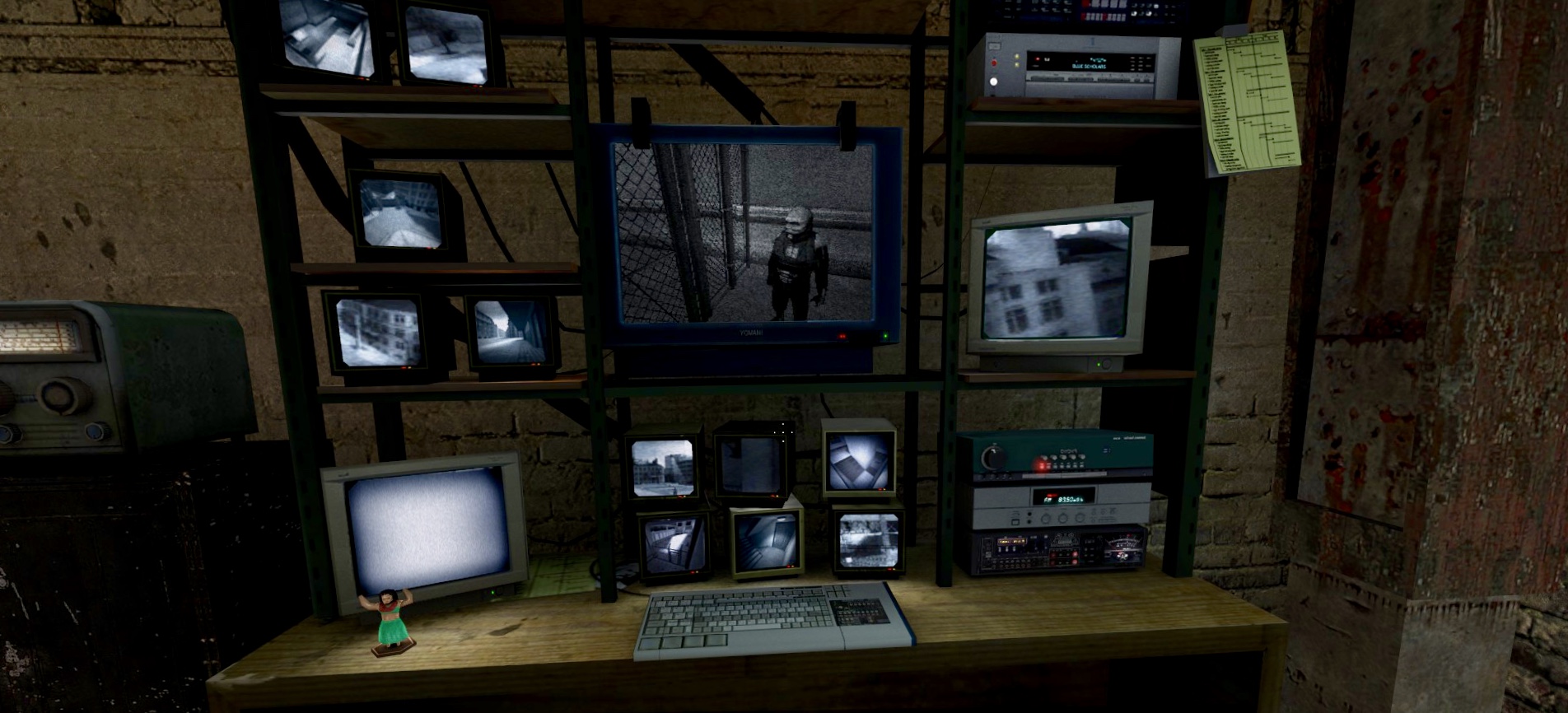

This is interesting for the process of documenting this world, since the act of photography helps comprehend the injustice of this world. In taking pictures of the City 17, one transforms into a spy that infiltrates the dystopian regime, uncovers its secrets and atrocities. Certainly, the photos you take have no consequence for the diegetic gameworld, yet it nonetheless offers a game of fictionality that stands in relation to the gameworld and its plot.

Half-Life 2 lets players enact the story of theoretical physicist Dr. Gordon Freeman in his struggle against human subjection to a merciless oppressive order. In what came to be known as the Seven Hour War, an alien race called the Combine invaded Earth and established a totalitarian regime on its surface. When players take control, the situation seems desperate, but a collective resistance instigated by Freeman culminates in humankind’s partial victory over its oppressors.

Part of Half-Life 2’s fascinating spell is that players discover a strange and unfamiliar world and assume a role similar to Gordon Freeman to whom this world is also unknown. In the vein of classical dystopian fiction, both Freeman and the players undergo a process of realisationthat will lead them to a better understanding of the dystopian gameworld and to eventual rebellion against its system. Specifically, in our times (with authoritarian and totalitarian regimes on the rise) the act of documenting atrocities and injustice is an important task, and this might help the game tourist to see her/his own world for what it is.

The Dissidents and their Virtual Camera

The ominous G-Man has set Gordon Freeman and players on their mission and into the nightmarish world where the events are about to occur. Once players take over Freeman’s body, they find themselves in a train heading towards City 17. It passes a grey, industrial area reminiscent of Eastern Europe. People look terrified. They wear blue uniforms and hold black suitcases. From a citizen, players learn that they are being relocated. But where to and to what purpose? This feeling of estrangement is underlined in that Half Life 2 assigns players a specific role the dystopian narrative normally reserves for its diegetic characters: the dissident. Most protagonists of dystopia are initially well-adjusted to their society and hardly see through its inner workings—but this state of mind will change. From their first sensations that something could be wrong with their world, dystopian protagonists incrementally come to see the truth of their situation.

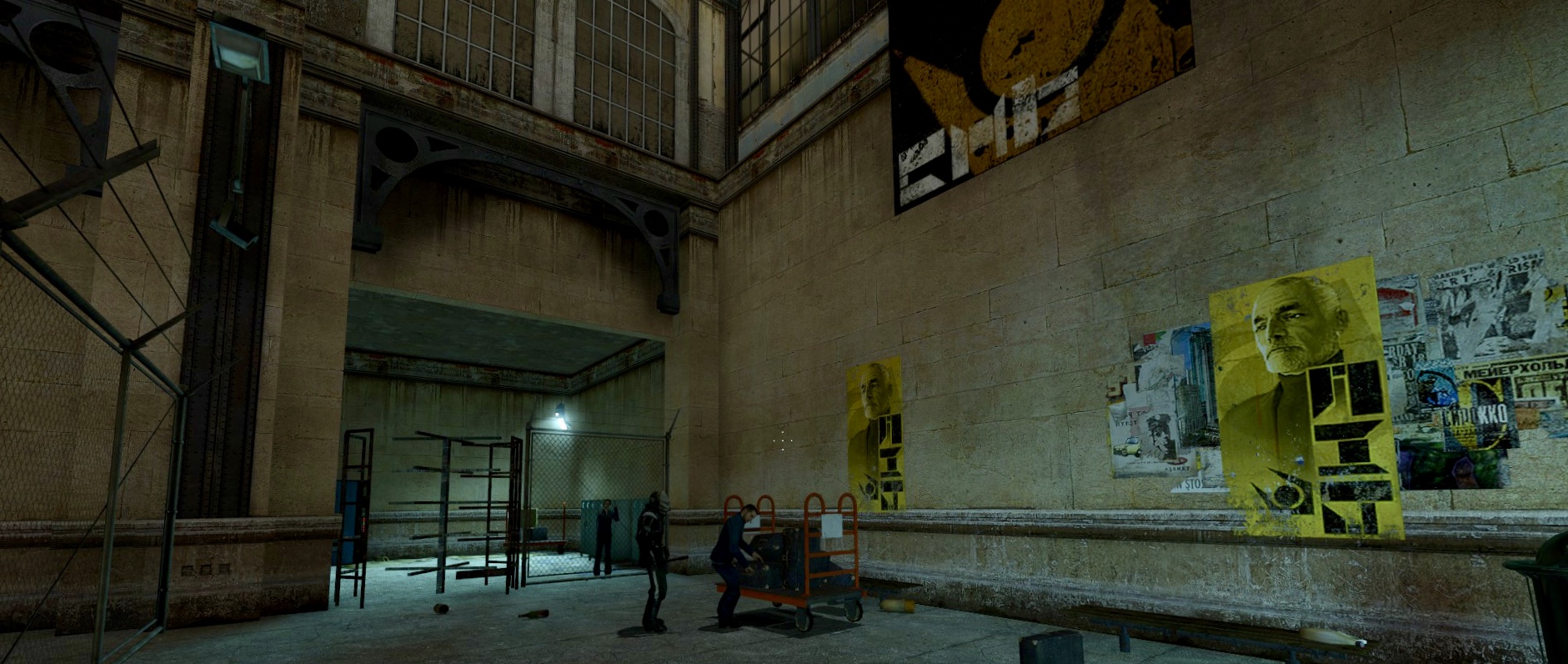

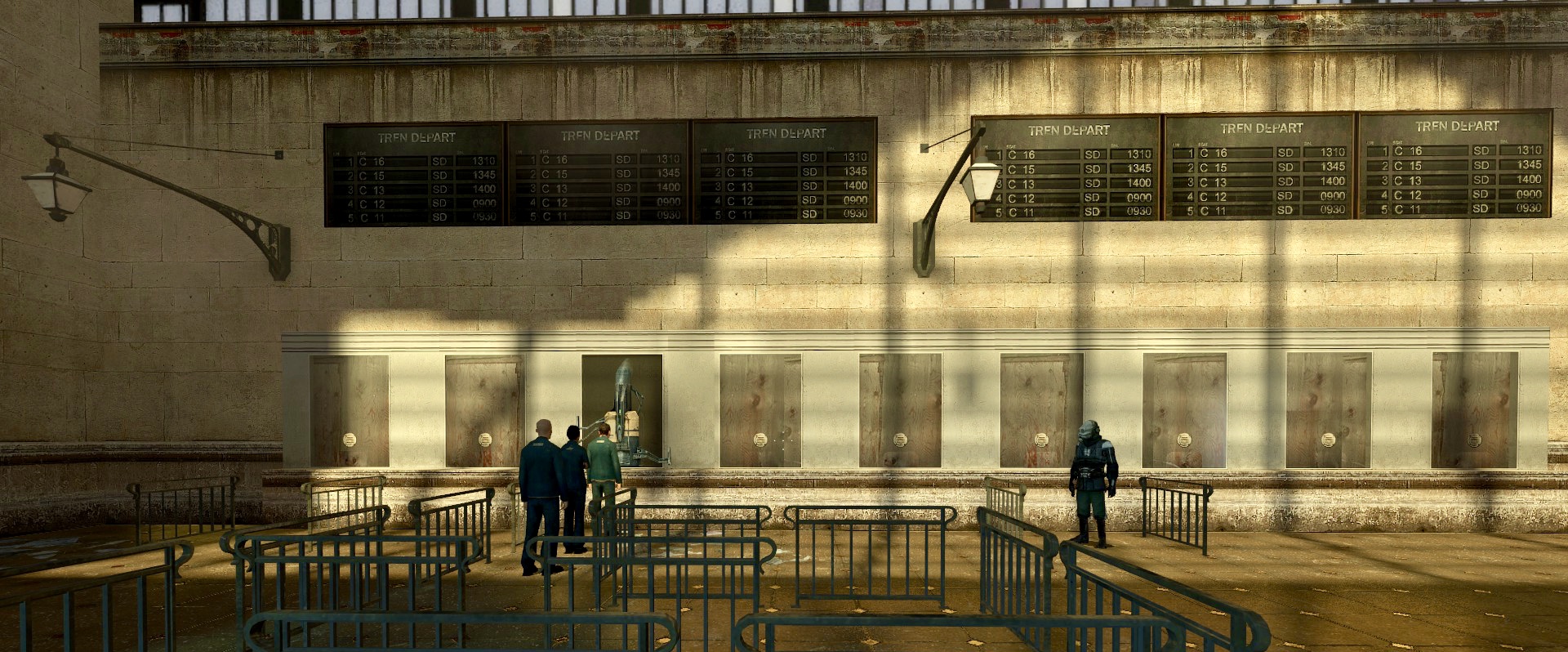

This continues when players aarrive in City 17 and experiences a merciless order. Having disembarked the train, a Scanner (a flying surveillance robot) takes pictures of its passengers, and a voice coming from a large screen welcomes her to City 17. Already in the first minutes of the game, the dystopian mode of Half-Life 2 is ubiquitous, and players quickly compose a negative image of this society in their mind.

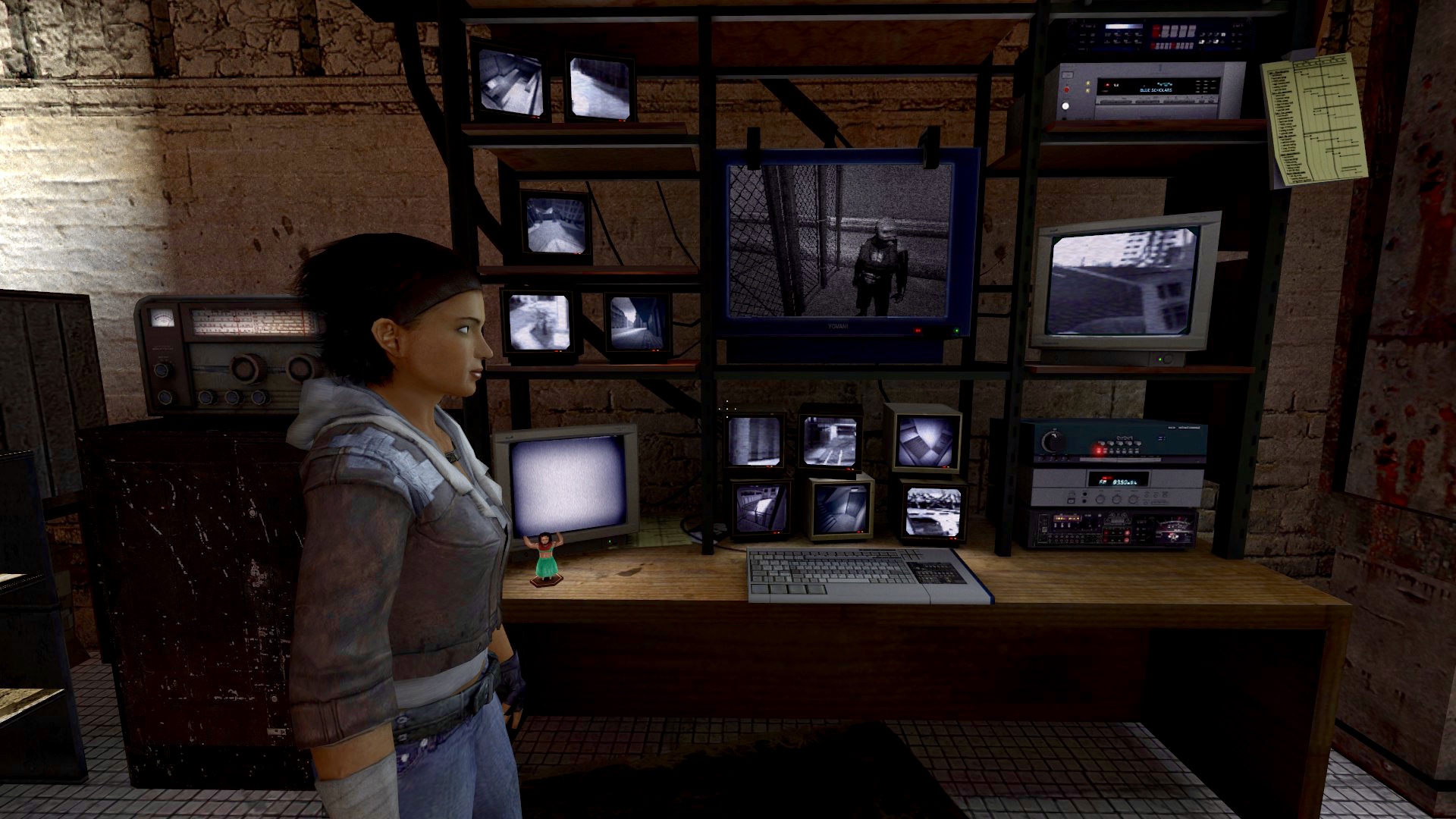

On Entering City 17, a bleak and derelict picture awaits. The train station resembles a prison, with fences and barbed wire on both sides of the tracks. Police forces are searching incoming passengers and do not hesitate to use their truncheons. They call themselves Civil Protection (CP), but what they do is question, torture, and murder people. Players experience these brutalities, as they are called in for questioning. Stepping into the interrogation room, terrifying expectations are aroused. Blood is spilled over the floor, and the CP officer asks for privacy. He switches off the surveillance cameras—yet, to the players’ surprise, the man turns out to be Barney Calhoun, a member of the resistance, who will help Freeman escape.

By experiencing the events of Half-Life 2, players may discern fundamental parallels with George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four. The game employs depressing spaces to raise awareness of the situation’s severity and depicts City 17 as an inhospitable location, whose run-down houses are juxtaposed with the towering Citadel, the glorious and phallic headquarters of Dr. Wallace Breen’s Earth administration. Indeed, City 17 explicates what Orwell’s London imaginatively implies and illustrates a misanthropic environment at the centre of which the oppressive order pompously rules.

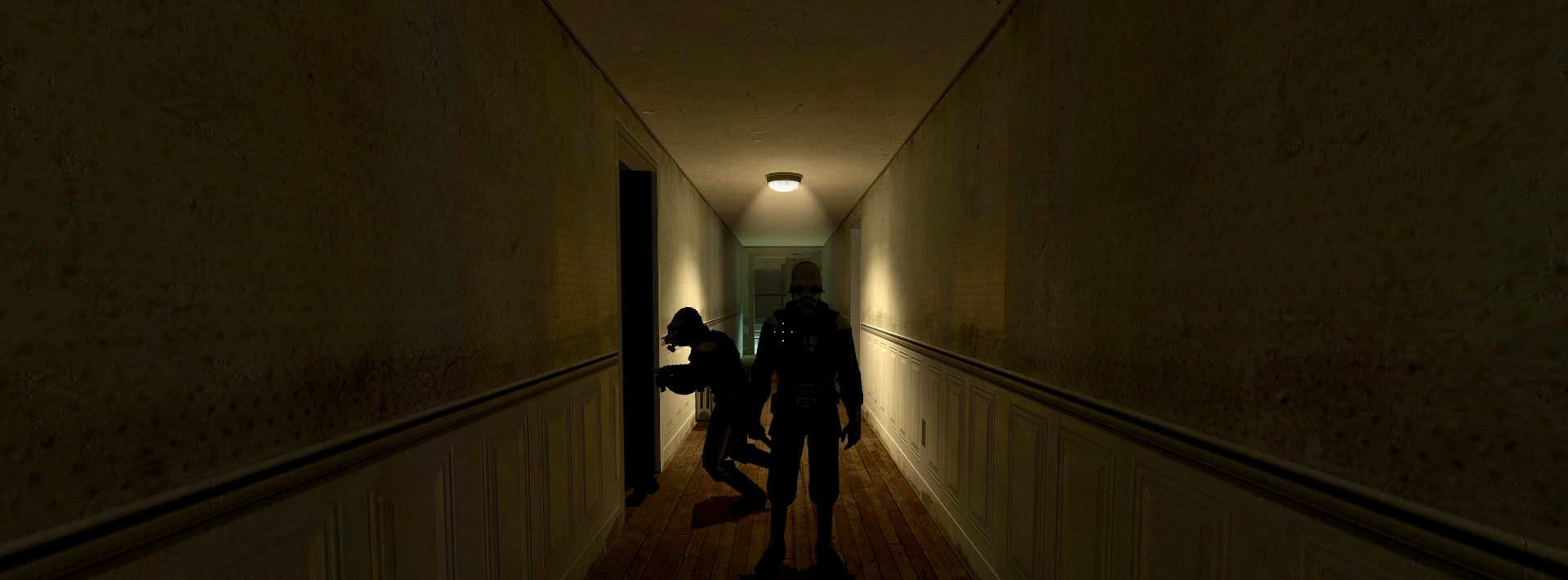

Dr. Breen assumes a role common to dystopian fiction. He represents anarchetypal father figureand the elusive leader of the dystopian regime and functuons as the Combine’s right arm. Like in Nineteen Eighty-Four, the Combine strivefor total outside and inner control, which is executed through the forces of the Civil Protection. In many ways, they are Half-Life 2’s thought police, wearing white gas masks and threatening black uniforms. People live in constant fear of the CP, as they intrude into their homes and torture their loved ones.

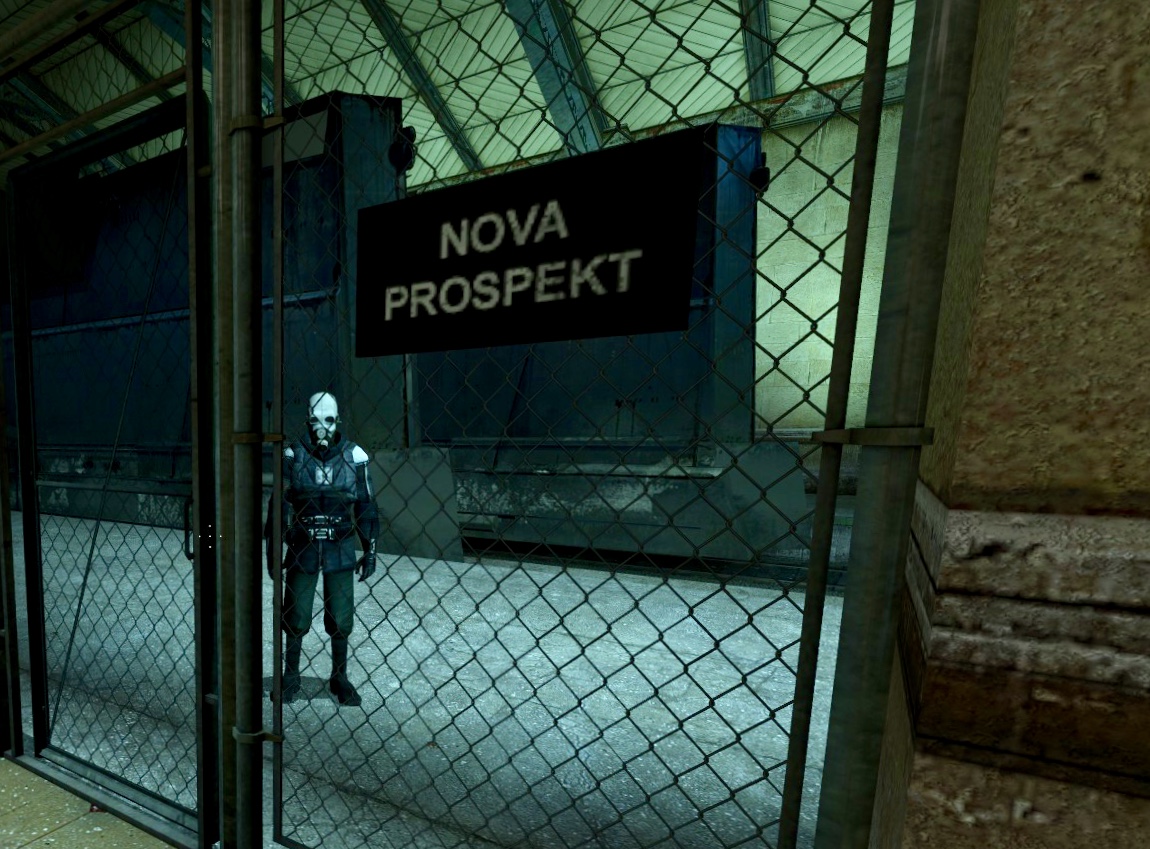

What terrifies most is the threat of abduction. Dissidents are transferred to the Citadel where they are murdered or held captive to undergo memory replacement. Given the Overwatch’s omnipresence, every inch of life is spied upon, and the intrusion into the private sphere is aggravated through the usage of Scanners. These are flexible variants of Orwell’s telescreens that take pictures of people’s activities or track down enemies of the state. In short, in the world of Half-Life 2, human spirit is broken, and the player encounters a highly regulated gameworld in which even cities and highways are numbered. But thankfully, it seems not everything is lost just yet.

The Counter-Narrative in Half-Life 2: The One Free Photographer as the Opener of the Way

On their trip through dystopia, game tourists gradually come to understand this world, which evokes in them the desire to rebel. The counter-narrative in Half-Life 2 begins with a minor but conceptually important event. When players leave the train at City 17’s train station, they encounter a guard that commands them to throw a can into a nearby trash can. Players may comply, but they may also resist and throw the can at the Civil Protection officer. They may be beaten in retaliation but their actions point towards a militant/resistant attitude and to a revulsion against the regime.

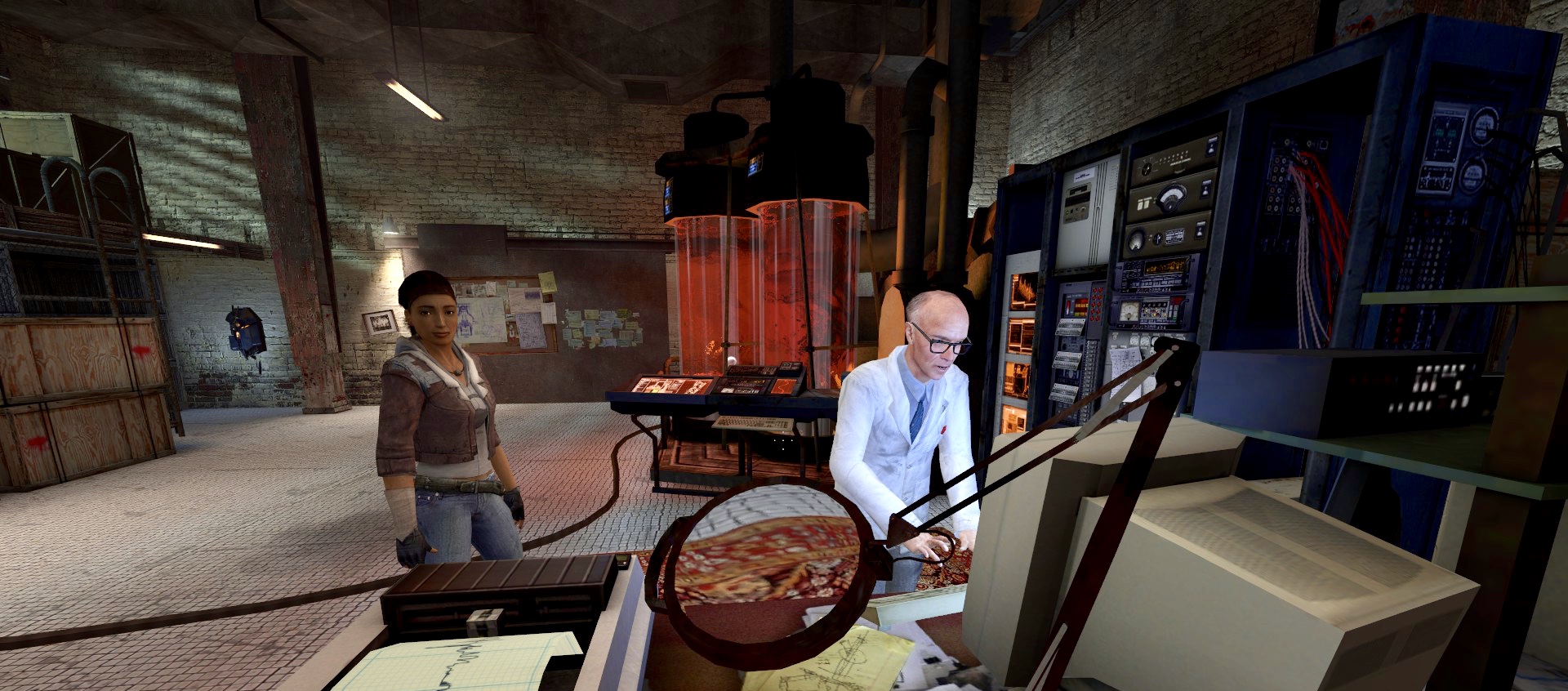

Alyx is a so-called companion character (the first of her kind in video games) and will accompany the players. In addition, she embodies an archetypal character of the temptress. In classical dystopian narratives, the temptressis most often a woman whom the main (male) protagonists meets and falls in love with—or establishes some sort of close relationship.

The temptress functions as a figure of guidanceas she charismatically helps the protagonist and reader gain insight into the dystopian situation of the fictional society. Thereby, her methods of seduction are diverse and range from enthusiastic, curious inquiries about the world—such as Clarisse in Fahrenheit 451 or Julia in Nineteen Eighty-Four, who both question the integrity of their society—to naive but nonetheless charming seductions in Planet of the Apes (Franklin Schaffer, 1968) or The Time Machine (H. G. Wells, 1895). In these, the female protagonists (Nova, Weena) foreground the society’s paralysis through their juvenile behaviour and evoke in the protagonist a revulsion to the society at hand.

In its first half-hour, Half-Life 2 thus manages to set the tone for the adventure to come and introduces players to a world that is in desperate need for revolution. The task of the game tourist, thereby, is to be a spy, to document this society and expose its inner workings and injustices. This act of transgression has spectators (of the created art galleries) work out the similarities between the virtual photography to their own society, and incites in them the need to act.