Metro 2033 (4A Games, 2011) is a nightmarish vision of a nuclear future to come as it is a depiction of humankind’s inability to evolve past vital shortcomings. The game involves players in a conflict between ideologies and several factions (the Reds, the Nazis, and so on) and asks the question how ethical can one act given such dire circumstances. In addition, paranoia has infested the Metro stations, for people are afraid of a race called the Dark Ones, which induce hallucinations in them through their psychic powers. There are plans to extinguish this threat once and for all, and the fear of Otherness is thus the central theme of Metro 2033 and premise to the game.

Players take on the role of Artyom and are sent on a mission to D6, where a final choice concerning the Dark Ones will be taken: wipe them out through nuclear holocaust (and repeat history) or spare the post-human race. The game, thereby, confronts players with two opposing positions and perspectives (those in favour of sparing the Dark Ones and those who wish to wipe them out) and has them negotiate the prospect of Utopia or Dystopia through their own actions.

Pictures are taken from the PS4 Version of Metro Redux (4A Games, 2014).

As a game tourist such a premise is fascinating for documenting one’s story and choices, but also to capture the mood in the Metro: the lives of its citizens and the sense of anxiety, the nightmare-inducing tunnels, yet also the prospect of hope when players act in ethical ways. These images, depicting the dark parts of the Metro, are juxtaposed to the phallic symbolism of the game (the tower, the weapons depicted from the first person perspective) and represent a journey into the deepest parts of the human unconscious, into the sins of our nature–an indeed alluring sequence of events to capture on virtual camera.

Life in the Metro

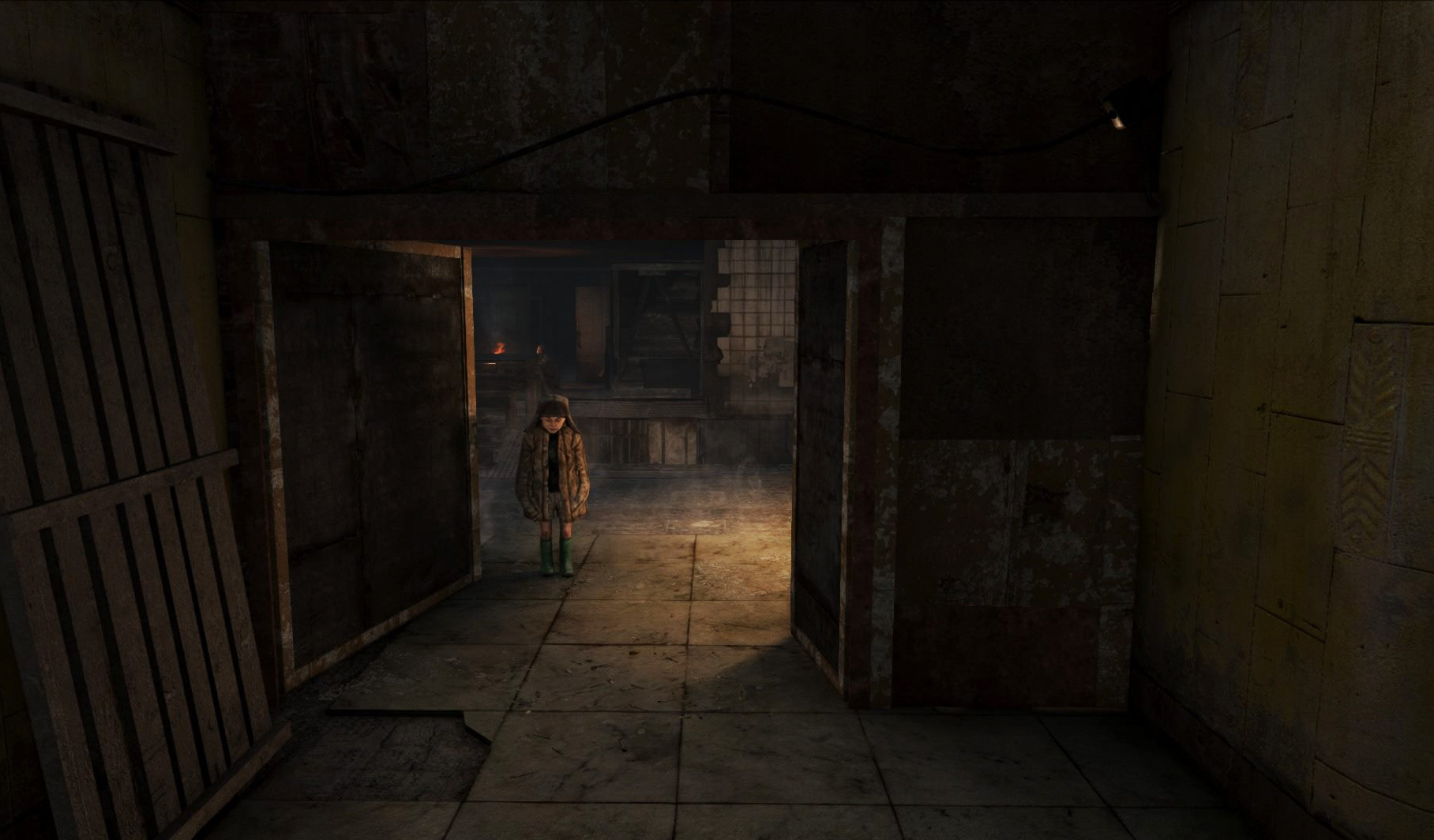

Most stations (such as Exhibition) have players witness and experience the misery of people and their suffering. There is chatter about disease and mutant attacks, while children cry in the background. People in Exhibition blame the Dark Ones for their situation, mentioning how they damage their prey’s minds through hallucinations. The existential fear of the Other is palpable in every respect, and the player passes a hospital area with men wounded by the attacks. What can be the solution to these issues, the player may ponder. For the situation is desperate and the station will no longer endure it. But looking closer, and into people’s eyes, sometimes reveals hope in even the most darkest places, when the tunes of a guitar have the young ones fascinated.

Descending into the deepest parts of the human unconscious

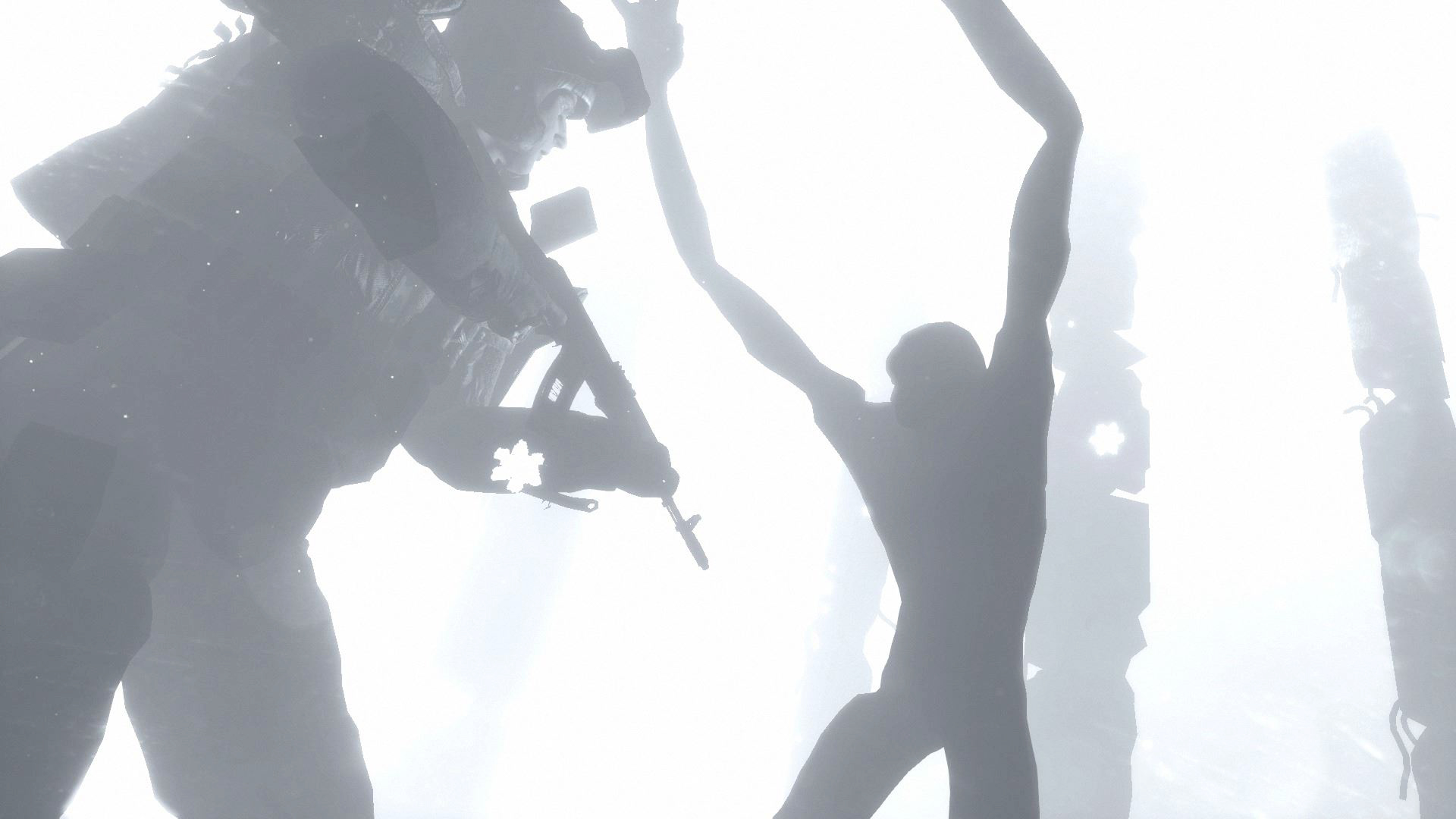

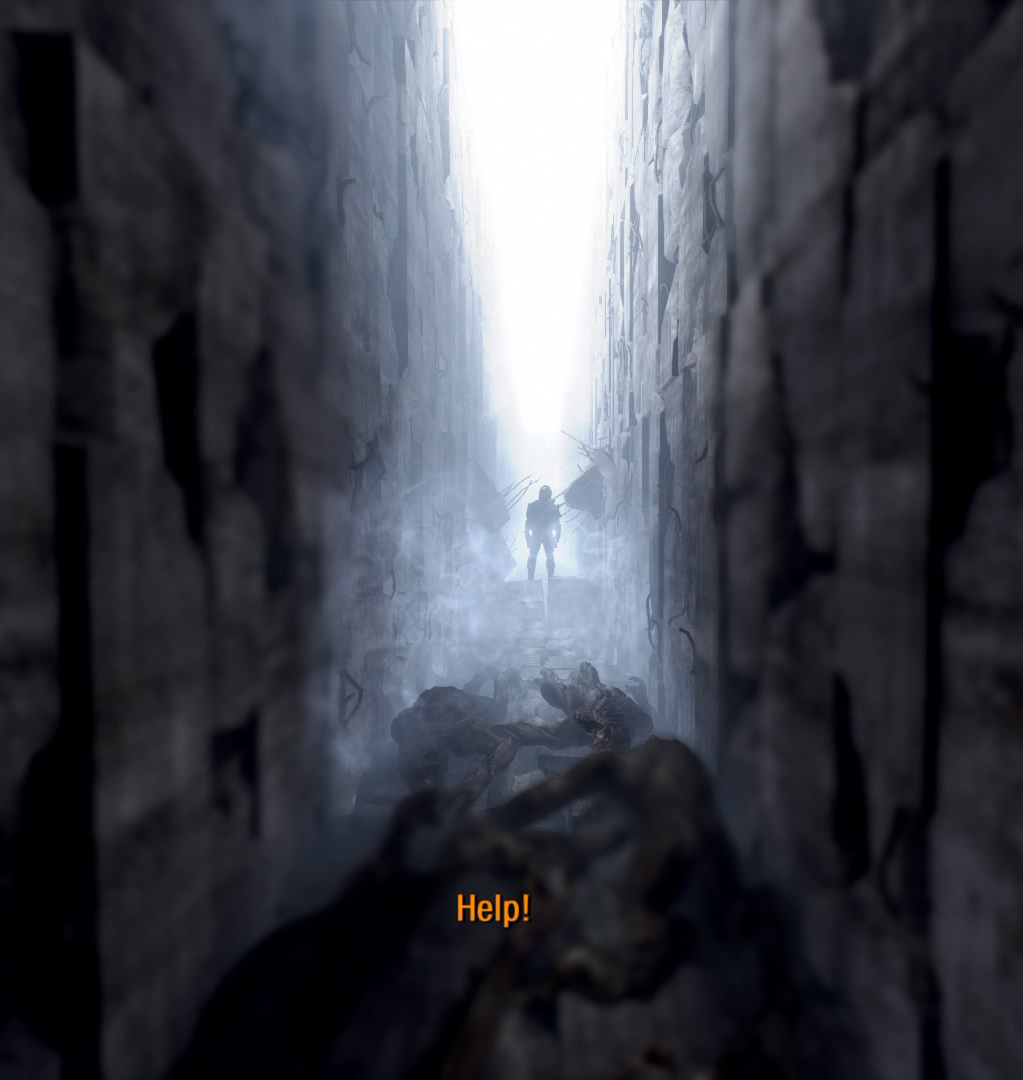

The conflict between the Dark Ones and the humans was caused by a misunderstanding, when the former approached the humans with peaceful intentions, but the humans were arrogant in their concept of humanity. Too afraid of change and driven by the anxiety of evolutionary defeat, the humans declined to accept the post-human solution the Dark Ones promised. As homo novice, the Dark Ones are better adapted to the new world, but they are a life form humankind does not understand (or does not wish to understand)—all of which the player is unaware of for now. The image captured here is ambiguous in this regard, having players ponder whether the Dark One is attacking or surrendering.

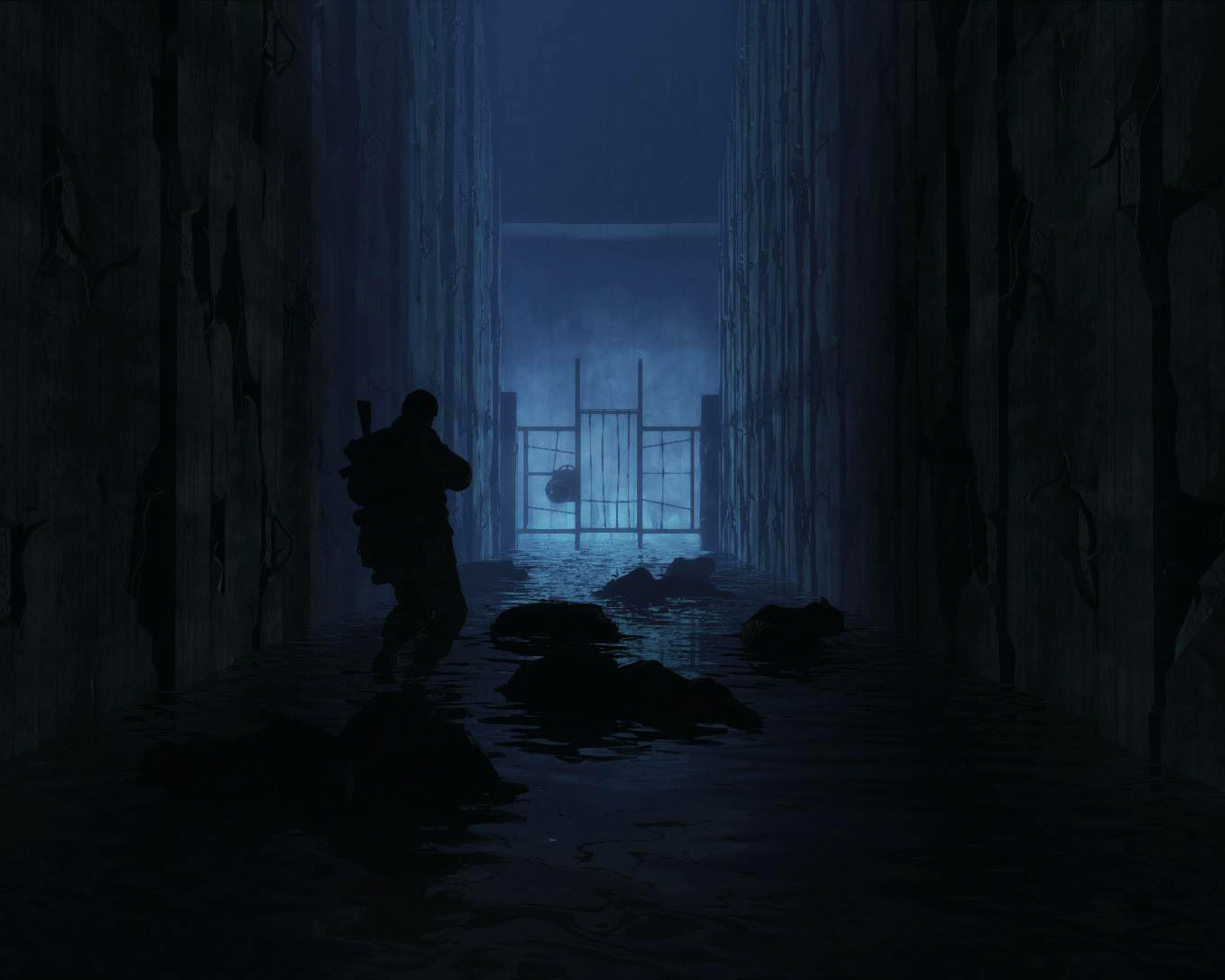

The never-ending battle at Cursed Station illustrates humankind’s struggle against the violent parts of their nature, in which monsters (the Nosalises, a common enemy in the game) continuously attack. They stand for those parts of the self that humankind cannot get rid of and that fundamentally revolve around the instinct of survival and the mistrust of the Other (an image players will steadily compose). After a barbaric slaughter, the section ends with players entering a shrine at the tunnel’s end. It is guarded by shadows of fallen men, and access to it is only granted to the virtuous and pure at heart.

A further image to illustrate humankind’s unwillingness to evolve is when players pass a bridge that is contested by both the Red faction and the Nazi faction. Not even the apocalypse could stop them from bloodshed, and the bridge creates a terrifying but, at the same time, beautiful image of the futility of these conflicts. Players may choose to either sneak below the bridge or participate in the frenzy of combat, but they will certainly ask themselves whether mankind is doomed to fight forever.

A further image to illustrate humankind’s unwillingness to evolve is when players pass a bridge that is contested by both the Red faction and the Nazi faction. Not even the apocalypse could stop them from bloodshed, and the bridge creates a terrifying but, at the same time, beautiful image of the futility of these conflicts. Players may choose to either sneak below the bridge or participate in the frenzy of combat, but they will certainly ask themselves whether mankind is doomed to fight forever.

Life outside the Metro is toxic; nevertheless (and because of it) these images exert a sense of the sublime, when terror evokes the emotion of astonishment. When players are about to reach the surface of what used to be Moscow, an intoxicating image awaits them. They put on their gas mask when a shadow, resembling a werewolf, bids them welcome to a frozen world.

Polis

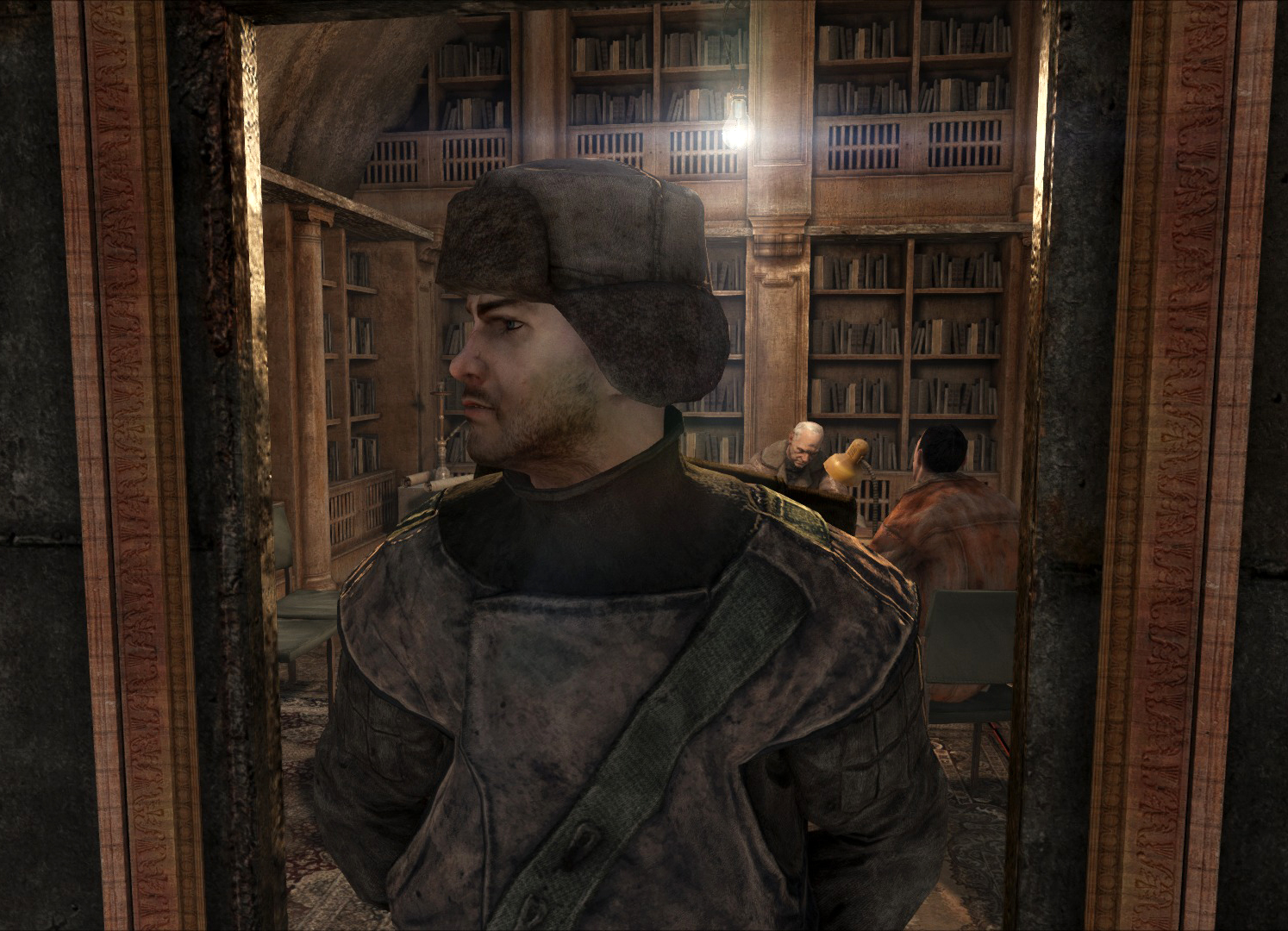

Polis is the centre of science and knowledge in the Metro. It is situated beneath the former Moscow State Library (a revelatory juxtaposition), and many scouting missions to extract its treasures are undertaken. However, although the best and brightest reside in Polis, they refrain from intervening in the issue of the Dark Ones, and, thus, the supposedly reasonable turn a blind eye to ethical issues.

Two perspectives concerning the Dark Ones

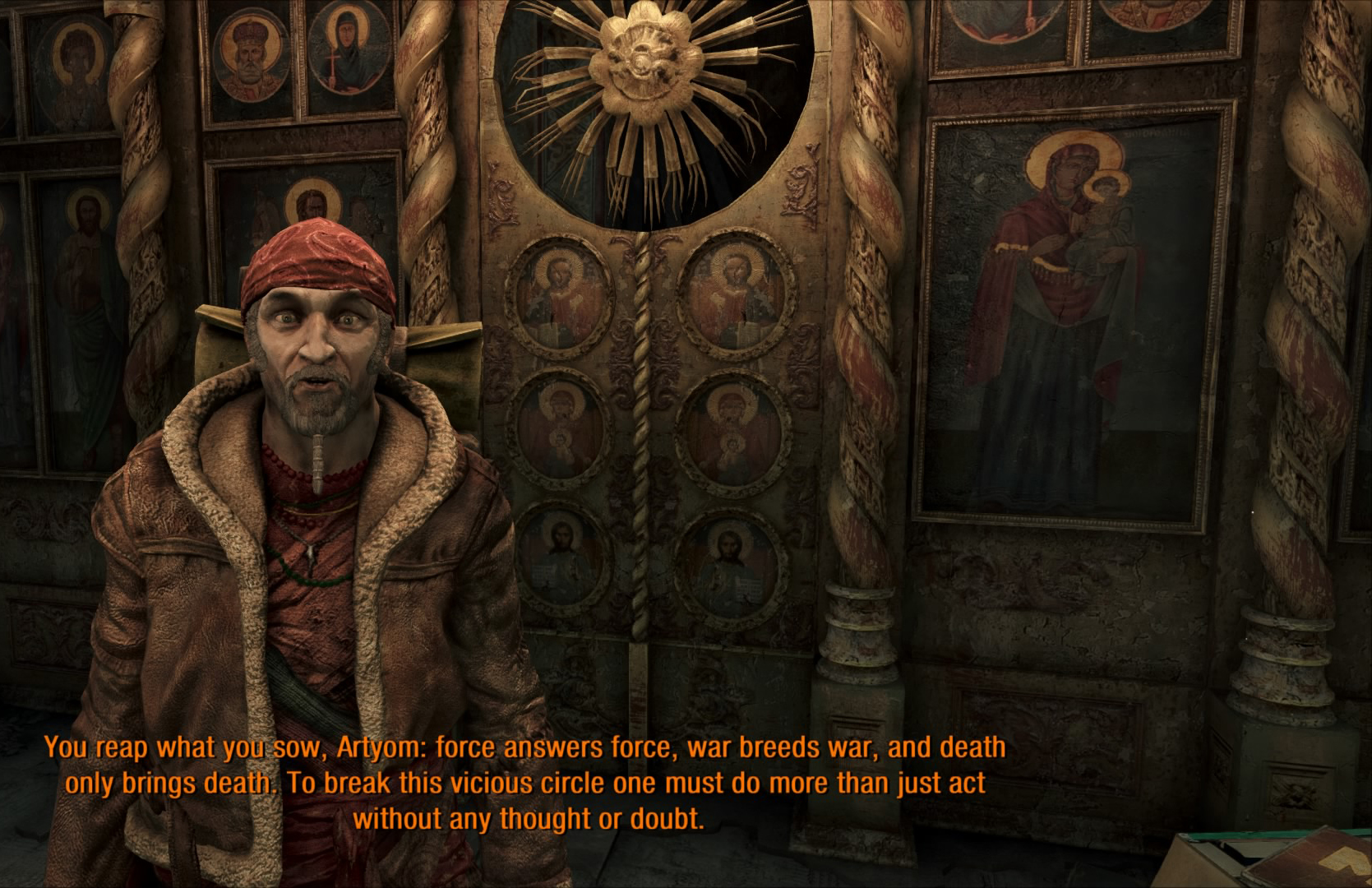

During the journey players meet Khan, who will become Artyom’s and their mentor. Khan understands the psychic phenomena of the Metro and warns Artyom on various occasions that force is not the answer and that to “break this vicious circle one must do more than just act without any thought or doubt.” The Khan chapters lead players into the darkest parts of the Metro and into the deepest spheres of the human unconsciousness. They illustrate that even beneath humankind’s ugliest parts lies hope in the search for compassion and in a cathartic cleansing of the aggressions towards the Other.

Shortly before the game’s final moments and the players’ ascension of the tower, Khan reminds Artyom of these truths. He therefore exhibits those characteristics of empirical society that aim at prudence and dialogue, not war and destruction. What enhances this image is that the conversation takes place in an old church underneath Moscow, which creates a beautiful inversion in that hell has extended to the surface of the planet, while only a few parts beneath it remain untouched. Khan’s perspective is thus to be seen in terms of an altruistic world view that promotes benevolence towards the Other and which stands in strong contrast to that of Miller, who has established a base of operations within the church.

As such, players are presented with two opposing perspectives that have plastered their way before and are set between the seemingly incommensurable fronts of war and peace and in an intricate game of agôn to which they can react. However, Metro 2033 does not make it easy for players to have a say in this choice, for only the virtuous and pure-hearted may take it and instigate a successful counter-narrative to this dystopia.

The final decision

To have a say in the game’s final choice, players have to behave ethically, and Metro 2033 pays close attention through a subtle morality system. It is the big choices but even more so the little choices that matter in a world of despair—and, consequently, decisions such as passing through certain areas without engaging in conflict, being generous to those in need by handing them ammunition or rejecting rewards for helping them, or listening to people’s problems (even to those of supposedly evil factions like the Nazis) will reward the player with morality points.

A most precious example of such is when Artyom walks past a derelict playground and a vision of the Dark Ones fills it with life and the playing of children. If players choose to relish this moment, and even takes off their gasmask, they will receive a morality point, or even two. If they rush through it, or shoot a bullet, the vision will end with a negative entry in the morality system.

Having almost reached the tower, Miller and Artyom are attacked by a demon. Miller is nearly killed in the encounter, but Artyom succeeds in defeating it. Players may now be filled with fictional anger for having almost lost a dear friend, while Artyom’s victory seemingly gets to his head. He now believes he is the strongest predator on Earth, and this frenzy of emotions is easily transferred to players and furthered by the rapid ascent of the elevator, which like a seminal fluid shoots Artyom to its peak. Consequently, there are two options for player: succumbing to irrational instincts and the frenzy of combat (such as Artyom in this instance) or remaining calm by having in mind the greater picture (what Khan told the player).

Even the tranquil race of the Dark Ones are becoming nervous in the face of potential extinction. Although their reaction depends on whether players show a positive or negative morality balance, they utter doubt in both instances—going as far as trying to stop Artyom by inducing hallucinations in him. Playing Metro 2033 is thus precarious. It is driven by uncertainty and the loss of a potential Utopia, and yet it appears inescapable that players have not become aware of these facts.

“If it’s hostile, you kill it!”